Is Our Activism Getting Us What We Want?

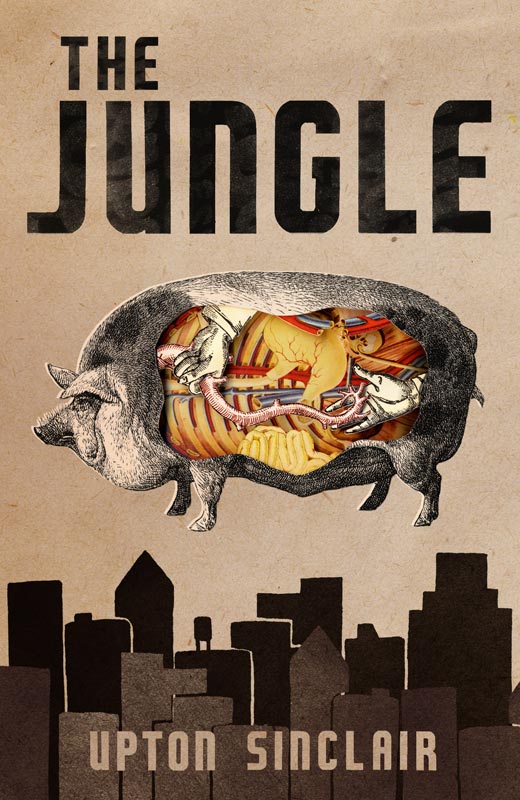

Regarding The Jungle, young Upton Sinclair (1878-1968) said, “I aimed for the public’s heart, and by accident I hit it in the stomach.” Despite its stark realism designed to produce sympathy for the working man, the novel disgusted its audience, who became more concerned about their food than about the degradation of the poor. Sinclair’s intended sweeping change in the workforce wasn’t really accomplished until FDR’s New Deal. This seems to be a pattern in history for widespread social change––it rarely works the way we would like it to. The context and consequence of The Jungle reminds us that as exciting as activism is, we should be wary of expecting instant and easy solutions to complex social issues.

The Jungle is best described as Socialist propaganda––a piece designed to shed grim light on the horrible treatment of the working man in the early 20th century. It describes the tragic story of Jurgis Rudkis, a Lithuanian man who, with a head full of “the American Dream,” experiences almost total debasement. The “dream,” as it turns out, is nothing more than a ploy used by Oligarchic systems to enslave hopeful immigrants. Sinclair spares none in his description of graft, greed, and hopelessness that plagued the period. When Jurgis’ life is at its most bitter low, he attends a socialist meeting. The clouds open up, the heavenly choirs begin singing, and God himself might as well be introducing the “pure” and “perfect” solution to all society’s problems. Says the narrator, “It was the new religion of humanity––or you might say it was the fulfilment of the old religion, since it implied but the literal application of all the teachings of Christ.” Such hope contrasted by 330 pages of utter despair is enough to activate even the most sluggish of pessimists. But is our activism working?

The Arab Spring, 2010. Twenty countries successively revolt against their governments. Boom, boom, boom. Firecracker-style. Six years later, several of them are still in crisis mode, and a couple are in an all-out war. Furthermore, there’s the up-and-coming extremist group, ISIS, which is hell-bent on asserting dominance not just in the middle east, but in the world. At what point to the flames of revolution become an uncontrollable inferno? And how “fixed” have those countries become?

With the advent of social media in this information age, social reform occurs at a rate and to a scale unimaginable by those in Sinclair’s time. What will be the costs to society of homosexuality, abortion, feminism, legalization of drugs, minimum wage hikes, gun control increased spending in social programs, and other hot topics on today’s polls? What will be the costs of keeping the status quo? Social media’s compact sensationalism is delivered to our inboxes at an alarming rate. With things moving so quickly, are we adequately reasoning through information before drawing conclusions? We are quick to click “like” or “share,” to swipe right or swipe left, to make snap judgements and rash conclusions. We know more about what is going on in the world and less about why it is going on.

The Jungle points clearly at a well defined corruption structure of the time: the Beef Trust. The slave-laborers of the trust were well informed about its graft and political involvement, having been part of it first hand. With the help of organized grassroots movements and Sinclair’s novel, Roosevelt was pushed to break the trusts. But today, corruption is a many headed beast with no real focal point. Our information is delivered to us second or third or fourth hand. It can be hard to trust the media delivered to us and even harder to trust corrupt institutions. Despite widespread litigation to curb corporate corruption, it continues to be a major force. DuPont, for example, a chemical company in the Northeast, continues to face

litigation for decades of pollution, dishonest practices, and shameful cover-ups. We’ve come a long way since Sinclair’s time, but we’ve a long way yet to go. This single book did not, indeed, cannot lead to the complete reform of the problems it describes, however influential it was at the time.

That’s not to say that activism and revolution is a fruitless and wasteful endeavor. It would be a gross understatement to say that activism is important in shaping history. But perhaps we would do well to slow down a little, to examine our outcomes, and to embrace the responsibility of what comes next. Though Jurgis Rudkis is saved from his miserable life by socialism, Sinclair himself resigned from the party when the execution of its ideals were not carried out satisfactorily. And truthfully, ideals will always be just that:ideals. The Jungle’s presentation of socialism is in form exactly the same as the

World Socialist Movement today, over a century later. These ideals have never been successful in practice and likely will never be, given the track record of Nazis, Communists, and extremists riding the waves of social change. Such change is important and necessary in an ever evolving world, and we should take part in it in an educated, calculated, and cautious way. There is no single blanket solution. Our efforts may hit the wrong areas. And like Occupy Wall Street, our activities may do little more than bring an issue to the tables of debate. But if we are wise and patient, we won’t face any derailing surprises.